Jobs-to-be-Done summary but for dating businesses

Inspired by the Intercom’s “Intercom on Jobs-to-be-Done” e-book.

Jobs-to-be-done framework isn’t a new thing and was created almost 30 years ago by Tony Ulwick. But in the beginning, it was used only for physical products and not software or online services.

A few years ago, Intercom, one of the biggest business messaging platforms, released a book on Jobs-to-be-done framework but for online software products, written by their co-founder Des Traynor.

Today, I decided to compile a summary of the book but considering the specifications of dating, social or matchmaking sites for you.

The most intimidating point of building a product is when you stand on the abyss of the unknown. You look forward and see nothing and everything at the same time. Jobs-to-be-Done is the light guiding you and your organization through the abyss.

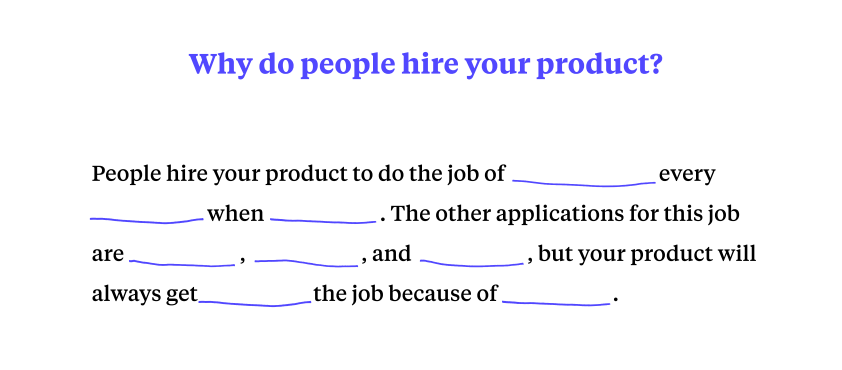

The main essence of this approach is very simple:

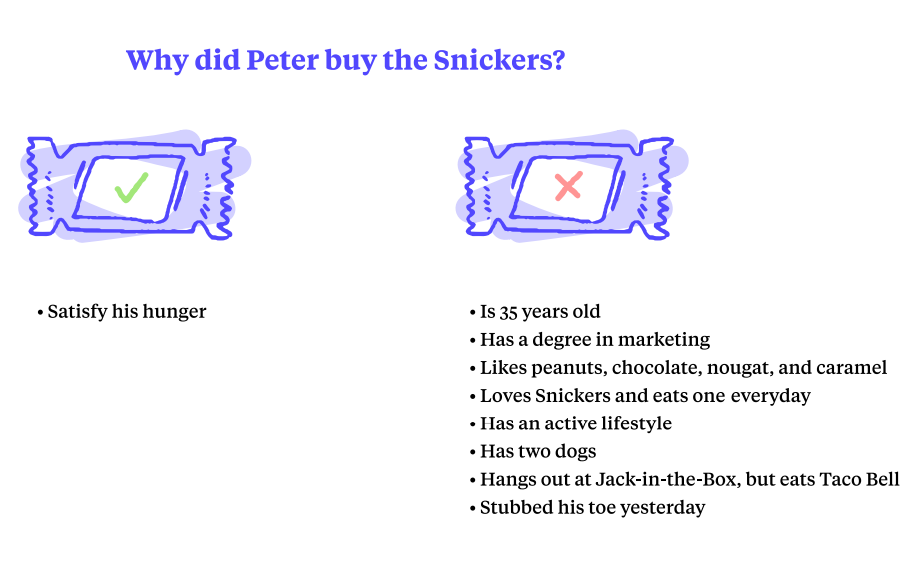

For example: Peter is 35 years old; he has two dogs. He’s hardworking, cheerful and kind. On Sundays, Peter goes to the gym.

5 minutes ago Peter bought a Snickers bar.

Did any of the characteristics listed above affect the fact of purchase? No, they did not. Peter bought the Snickers because he was hungry and not because he was 35 years old.

The point is that we all constantly have some kind of tasks (“jobs” in JTBD terminology): to kill time when standing in line; make a healthy breakfast; share your trip photos.

When we start using a product or a service, we essentially “hire” it so that it helps us do some specific “job”. This product does not match the person or his features, it matches the problems that it solves for its users.

The jobs-to-be-done framework helps you limit your imagination and focuses only on what really matters. People don’t use your dating service because it looks cool, have awesome features or 100 other features you have in your head, they buy it to receive the “Expected outcome”. People don’t buy the $99 premium membership on your site to have all 20+ features available, they buy it because it helps them faster find a love of their life, or a one-night hookup or lifetime friends and etc.

When you’re solving needs that already exist, you don’t need to convince people they need your product.

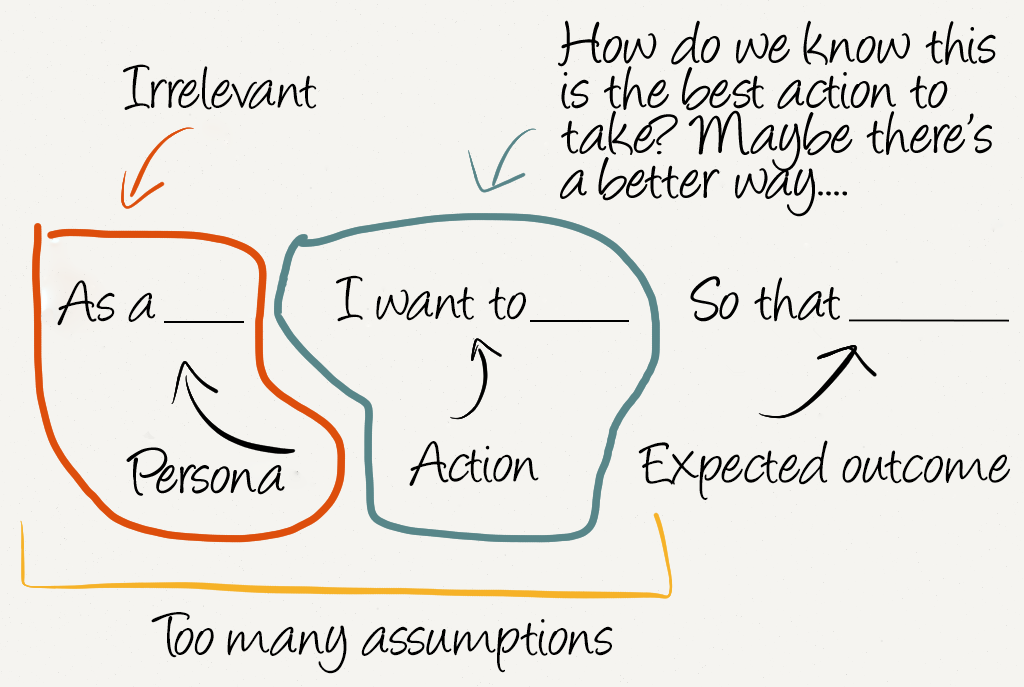

Personas: pros and cons

A persona shows what you know about your typical end-user. For example, Eastern European brides site has two typical personas: 1) young and beautiful Ukrainian or Russian lady, and 2) wealthy West European or American man.

An important detail is to make a persona as informative as possible, without any nonsense. For example, saying the user is 72 could imply you need to cater for diminished eyesight and low computer skills.

Pros: personas maintain the necessary level of empathy in the team, especially for those who do not directly communicate much with users, like developers or marketers.

Cons: personas artificially break apart audiences and limit your product’s audience by focusing on user attributes rather than their motivations.

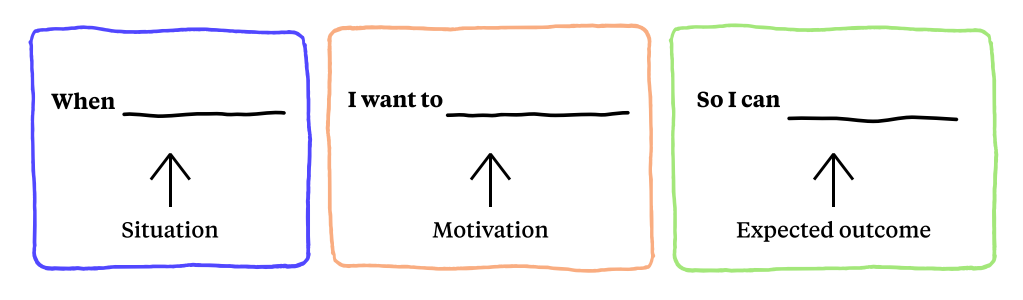

And here’s when the Job Stories are more relevant than personas.

Job stories

Here is a very clear example of job stories from the Intercom’s e-book:

Clay Christensen, Professor at the Harvard Business School, describes this as job-based marketing. He offers a masked example of a fast-food chain looking to sell more milkshakes.

Their initial approach was to study the users and make changes based on demographic analysis, customer analysis, and psychographic variables. This failed, and they sold no extra milkshakes.

There was no meaningful insight to be found in analyzing the users themselves. Instead, Clay suggested they focus on the job customers hire a milkshake to do. It certainly sounds weird (no one thinks of “hiring a milkshake”) but switching perspective offers new insights.

It turns out more than 40% of milkshakes were hired first thing in the morning – to provide sustenance for a long commute. So milkshakes were actually competing with bagels, bananas, and energy bars, rather than the rest of the chain’s breakfast menu. Milkshakes had advantages over energy bars and bananas – they’re tidier and easier to consume in a car. They beat bagels – they’re too dry and leave you thirsty. And they beat coffee – they’re more filling and don’t leave you desperate for a bathroom in the middle of a 40-minute drive.

Once the chain realized this, they were able to make changes that made milkshakes the best tool for the job – a convenient, easy to consume snack to stave off hunger till lunch.

Switching users to your service

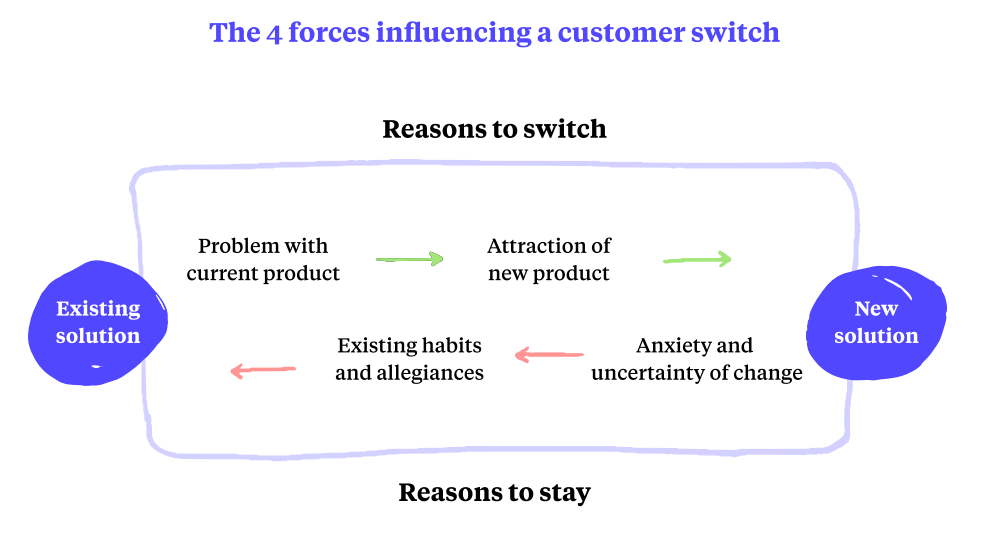

People are creatures of habit. They do things like they are used to do because the cost of reassessing their options every time isn’t worth it.

Switching is also about removing fear or hesitation associated with trying out your product and making sure you remind them of the problems with their current solution.

Advertising lets you manipulate these four forces. Specifically, you can:

- Increase the push away: Show how bad their existing product really is.

- Increase your product magnetism: Promote how well your product solves their problems.

- Decrease the fear and uncertainty of change: Assure consumers switching is quick and easy.

- Decrease their attachment to the status quo: Remove consumers’ irrational

attachment to their current situation.

Apple’s “I’m a Mac” campaign was hugely successful. It highlighted the pain points of Windows (1), demonstrated how great a Mac was (2), showed how easy it was to switch (3), and presented those who wouldn’t switch as buffoons, reducing their attachment (4) to old habits:

For any declarative statement, you might make, I can’t stop myself from asking “Why?” and then, I’ll ask “Why?” again. It’s an occupational hazard.

So you bought an electrical drill? Why? Oh, because you want to hang some framed photos. Why do you want to hang framed photos? Oh, to make your home more personal. Why is making your home feel more personal, important to you?

When it comes to product design, there’s such a thing as getting down to the root problem too quickly. The value in figuring out the “Why?” behind things isn’t so much about the destination; it’s about the journey.